As a series of events sent shockwaves globally, a large-scale process proceeded in the background imperceptibly, with the creation of new forms and methods to manage social phenomena, to all intents and purposes representing the birth of a new type of political system.

It has been clear to everyone that political systems in Western countries have started showing signs of strain during the past decades — and have been malfunctioning. Externally, this was manifested in the inability of political systems to effectively counter manipulation by forces and factional groups extraneous to the previous balance of interests.

POLITICAL ENTROPY

Digital technologies and the globalisation of disorder

- INTRODUCTION

- ON THE POLITICAL SYSTEMS OF THE NEW AGE

- THE PANDEMIC AND POLITICS

- INFORMATION OCHLOCRACY

- THE NEW AGE ECONOMY

- MASS PROTESTS AND THE MODERN WORLD

- WHAT SHOULD BE DONE? INSTITUTIONALISATION OF VALUES

It goes without saying that fringe politicians with authoritarian views have always existed. However, now they have started assuming far more substantial roles in their own countries and have already started forming coalitions between each other. The key factor uniting these politicians is a rejection of the significance of and even need for the European-style political system that appeared after World War II, and repeated attempts to present this system as “wrong”, unfair and unviable. There have been more than enough examples: Donald Trump in the USA, Boris Johnson in Great Britain, Vladimir Putin in Russia, Recep Erdogan in Turkey, Andrzej Duda in Poland, Viktor Orban in Hungary, and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

It does not always involve outright rejection — frequently these ideas are veiled under calls for “reform” of the political system. In most cases, this is manifested in the form of populism — calls for the restoration of the primacy of the interests of the people (for example, “Brexit”), juxtaposed against a corrupt and egoistical “elite”, and promises to make this happen if elected. At the same time, in most instances, the “people” that is referred to does not mean the entire population, but instead the so—called “real” people (“true”, “with core beliefs”), who are proponents of the “right” traditional values. Moreover, such people oppose not only the elite, but also other “foreign” elements and values. The intention here is not to satisfy the demands of the whole population, where you will find diverse minorities and special groups, but only its ‘core’ part defining state identity.

It is notable that in such cases as a rule the changes imply not so much the establishment of some new, more progressive and just order as the restoration of some old order that had allegedly been lost for good. In this sense the new populism (incidentally like its forerunner) addresses the past, some more natural, but lost order which had allegedly ensured justice and greatness at some point in time. And this represents the core of the explicit anti-globalism of the new populism, its focus on national historical values, calls for the restoration of former glories, which are as a rule dubious from the perspective of the values of humanism, and to a large extent mythical (“again policy”)1See Grigory Yavlinsky, Loss of the future, 2017 .

However, populism (based on the above understanding) is not the only phenomenon reflected in the increasing rejection in Western countries of the values of the political structure of society which gained a foothold after World War II in developed parts of the world. Another key symptom of today’s political about-turn has been the negation of the values of private life, disregard for privacy and autonomy as an indelible right (and to a certain extent attribute) of the individual.

As such, it is namely the separation of private life from public life, independence of private life from public dictates and control which represented the most important element of the concept of political and social progress throughout the 20th century. However, in the past decade the freedom of private life as a value has become a target of contempt, if not actual repudiation. Against the backdrop of the unprecedented and rapid expansion of opportunities for official and unofficial structures (and also the specific individual actors behind them) to control the actions and thoughts of individuals, resistance to such processes turned out to be surprisingly weak and impermanent. Most of the population was subconsciously already prepared for an intensification of controls — both physical, and also cultural and spiritual — in exchange for home comforts and social prestige, which is frequently illusory or confined to a narrow group. Moreover, opportunities for the integration of the spiritual lives of individuals on large-scale single platforms, which are comparatively susceptible to control and external influences, began to be perceived as a public achievement and form of progress.

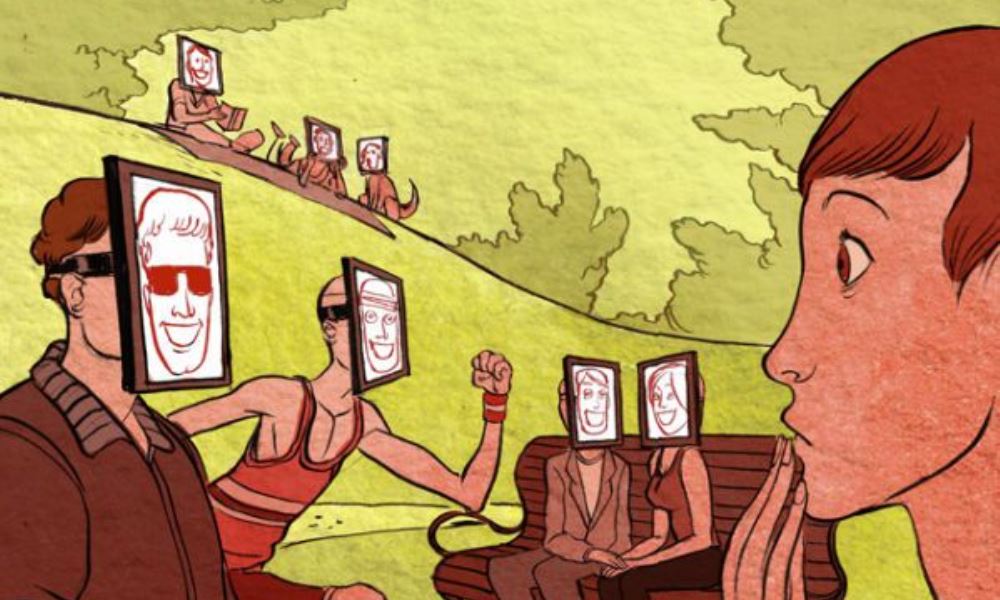

Finally, another key aspect of Western political structure of the second half of the 20th century, which has been significantly weakened over the past decade, was the hierarchical nature of the organisational system for running society. The “networking” of society2The Dutch sociologist Jan Van Dijk determines a “network society” as a society where a combination of social networks and media networks shapes the key form of organisation and where they represent the most important structures at all levels (personal, collective and public). By contrast a mass society is shaped by groups, organisations and communities, arranged through physical co—presence (Jan Van Dijk, De Netwerkmaatschappij [The Network Society], 1991). so typical of today, accompanied by a wide distribution of forms of influence, and accordingly a decrease in individual accountability, has ambivalent consequences. On the one hand, traditional leaders who have aspired to leading roles in a vertically organised society lose the opportunity to influence public moods and political decisions to the extent that they could in the past. On the other hand, utterly random people are promoted to the role of leaders (often impromptu individuals or so-called “men of the people”), who just happened to be at the crossroads of different networking platforms.

As a result, there has been an abrupt increase in the number of random outcomes in political systems unrelated to the actual balance of interests of public groups. More and more opportunities appear for fringe players and irrational actions, for virtually inexplicable and at times strange political decisions attracting unexpected support and a chance at implementation. Presented by enthusiasts as a tool democratising governance, in reality, “networking” generates chaos and irrationality and fosters growth in random movements frequently initiated by the beneficiaries of such destabilisation, whose goals are diametrically opposed to public interest.

Why have we witnessed all these phenomena over the past decades? There is no unambiguous response to this question if only because too little time has elapsed to draw final conclusions both on the substance of this process and also on its causes. Nevertheless, some explanations can be found, which are worthy of consideration.

All these developments can be attributed to processes frequently called the fourth industrial revolution, specifically the impact of new generation information and communications technologies on the social and political sector related to the expansion of the internet, the opportunity to collect and process large arrays of data, and use elements of artificial intelligence. These technologies, adapted for use in mass communications, triggered the dilution of the foundations of the “classical” Western model of political organisation of society (See «Information ochlocracy»).

How?

Firstly, information and communications technologies made it possible to “network” social communications in society: without the internet and its potential, there would be no social networks where anyone can announce their political ambitions and address a mass audience without any public mandate to engage in a political career. For example, today an unknown young ambitious activist can access an audience running into millions: if in the right place at the right time, such an individual just needs to make a little effort and be lucky. These days there is no need to spend countless years climbing the rungs of a party ladder or embark on a painstaking administrative career, meticulously establishing vertical and horizontal ties, and proving leadership skills and business qualities. All an individual needs to do is simply attract the attention of a group of active users through a striking image — and the viral dissemination of content will transform any such random individual into a political figure and a public opinion leader. Previous filters operating on the basis of financial control and selection criteria no longer work.

Secondly, information and communications technologies eliminated the tried-and-tested age-old system for influencing the public mood of using informal leaders of local and professional communities — or to put it more simply, authoritative figures for different population groups. Online any informal leadership is diluted and gives way to the political and behavioural patterns of a loosely organised crowd. Meanwhile, everybody knows that a crowd does not tend to a react in an orderly manner to significant political events and is unable to support rationally planned protracted campaigns, but is by contrast a pushover when it comes to incidental issues. Naturally, such communities can also be successful targeted. However, the tools available to achieve such an impact have little to do with the logic and structure of a party representative system.

Thirdly, another attribute of the new forms of communication concerns the disappearance of any hierarchy regarding the significance of events. I am not talking about the so-called gutter-like journalism spewed out for the mainstream audience, but rather the fact that this agenda is incapable of ranking events by their degree of importance. Data flows are being transformed into anarchic batches of messages/reporting and interpretations of such reports where news of utter irrelevance from a social perspective is mixed with events that could have significant implications for millions of people. Both online, and also offline in the traditional mass media in new information formats (for example, socio-political talk shows or continuous “news” broadcasting on TV channels), political events are presented in a cynical diverting or overtly perverse form — on the same level as standard entertainment; propaganda is jumbled up with advertising that debases its own content; gimmicks deployed to attract the attention of the average consumer (increase ratings, offline and online traffic) openly take precedence over the substance of the information. As a result, comparatively streamlined and ranked knowledge on the life of society is replaced by an endless entertainment spool of words and images, interfering with real news and at times rendering any understanding of developments and their potential consequences impossible.

Fourthly, the virtualisation of social interaction releases the negative energy previously suppressed to a significant extent by physical personal contacts between different sections of society. It goes without saying that such phenomena as “hate speech”, “trolling” and others are nothing new. However, they are becoming far more common and hostile in the absence of direct physical interaction. For the time being the political consequences of this phenomenon are not entirely clear, but there is no doubt that this will undermine the effectiveness of tools used in traditional party and parliamentary systems. The radicalisation of political conflicts, perception of such conflicts as an uncompromising fight between “us” and “them”, incompatible with the substance and intended purpose of such systems, render these institutions dysfunctional and meaningless.

Yet there are reasons to believe that the development of technologies is merely a factor creating a favorable terrain, while the failure of human consciousness to catch up with the achievements of the 4th industrial revolution is playing the decisive role in this turn of events.

For example, this is expressed in the generation gap — when the older generation is incapable of fully recognising and accepting a world that is changing so rapidly, while the young take everything for granted. However, instead of looking for answers to the questions “What is the point?”, “Why?, “Is this actually needed?” and “Could things be done differently?”, the new generation is preoccupied on how best to leverage the “rules of the game” which are already equated to the insurmountable laws of nature.

People believe that algorithms are replacing institutions and bringing happiness to mankind; that there will be no need for politicians, scientists, doctors, teachers, institutions and systems; that their places will be taken by technologies which will be available to everyone: given that everyone has a gadget that can be used to download apps, this means everyone can use the algorithm, and that everyone in future will be able to print whatever they want on a ЗD printer…

In any case, all these factors demonstrate that the crisis of party and parliamentary systems in leading countries in the West is not some accidental short-term aberration. It is the natural consequence of the expansion of new information and communications technologies in the political sector, and accordingly represents a serious challenge for the future. The Western political system was also simultaneously a representation system of the boundaries of what is permissible in politics, in other words more or less sustainable boundaries that an individual could not transgress without being cast out of the system.

These boundaries have expanded significantly with the emergence of the current generation of populist politicians. At the same time, however, today the system is not discarding the people who have been expanding them. And most importantly, nobody knows how widely the boundaries can be expanded right now. Can any information be disregarded just because it has been called fake? Can a law be declared wrong/unjust and not be implemented? Can we simply refuse to recognise the results of elections? Can rules actually be changed unilaterally, with total disregard for previously established procedures?

For the time being nobody knows the answers to these questions. However, if all the above is possible, then this will already be a different system. Fundamentally different, even though formally all previous institutions will be retained: parliament, the judiciary, etc.

And this in turn brings us to an important question: what will come after Trump? Will America remain the same as it was 10-15 years ago? For if the boundaries of what is permissible have already expanded, who will move them back and when? Will this be done by the new elite — the “geniuses” of high-tech and Fintech? Will they actually want to spend their money, time and efforts to bring back the old times? Or will they be inclined to think that new times are coming when the world will be run by the creators and owners of artificial intelligence who dispose of an unbelievable quantity of information on people and their money and boast unimaginable opportunities to process such information, and certainly not “archaic” parliaments and the “antiquated” press? And will there be any need for law and order in its traditional form when information technologies can be used to directly control mass behaviour? Will the people holding themselves to be omnipotent actually perceive any need for checks and balances?

Incidentally, when present-day populist politicians like Donald Trump expand the boundaries of what is permissible in politics to fit their needs, objectively they also expand the boundaries for their opponents. And after Joe Biden’s victory in the US presidential elections in 2020, it is highly unlikely that they will move these boundaries back voluntarily. No individual would voluntarily forego such opportunities — other than some maverick idealist, but this is highly unlikely. Society will also not demand any narrowing of the boundaries of what is permissible, as it is splintered and is no longer capable to engineer a hierarchy-based organisation of society’s proactive and engaged participants, because all their energy has been squandered online, freeing up in the process the offline space for asocial elements. Meanwhile senior management of modern businesses has no interest in any boundaries, because they are not run by individuals like Rockefeller or Morgan, but instead by people like Zuckerberg and Bezos who do not believe in checks and balances for politicians, and instead worship the magic of technologies and social engineering. Against this backdrop, the disintegration of the previous political system is likely to continue, regardless of the outcome of the US presidential elections in November 2020.

We have all the grounds for assuming that the world in actual fact will no longer resemble what it has been in the past. And this has nothing to do with the coronavirus epidemic.

POLITICAL ENTROPY

Digital technologies and the globalisation of disorder

- INTRODUCTION

- ON THE POLITICAL SYSTEMS OF THE NEW AGE

- THE PANDEMIC AND POLITICS

- INFORMATION OCHLOCRACY

- THE NEW AGE ECONOMY

- MASS PROTESTS AND THE MODERN WORLD

- WHAT SHOULD BE DONE? INSTITUTIONALISATION OF VALUES