We are witnessing before our very eyes a serious transformation of the information and communications space which has already led to notable political and social changes and may have even more significant consequences in the medium and long term.

Drawing on the example of the mass media, one can track the extent to which serious changes have happened over the past 50 years.

POLITICAL ENTROPY

Digital technologies and the globalisation of disorder

- INTRODUCTION

- ON THE POLITICAL SYSTEMS OF THE NEW AGE

- THE PANDEMIC AND POLITICS

- INFORMATION OCHLOCRACY

- THE NEW AGE ECONOMY

- MASS PROTESTS AND THE MODERN WORLD

- WHAT SHOULD BE DONE? INSTITUTIONALISATION OF VALUES

Firstly, the flow of information is now based on opinions and derivatives of such opinions, instead of actual events (the reactions of some people to the opinions of other people: “rejected”, “denounced”, “ridiculed”, etc.).

Secondly, the mass media reneged on the function of classifying and hierarchising reports which had been mandatory in the past (for the serious press). Now reports and opinions follow in a continuous stream, and no attempt is made to rank them in terms of significance and relevance.

Thirdly, “virality” has become the norm, when one comments snowballs into strings of dozens or even hundreds of other comments: comments on comments, comments on reactions to the comments, comments on reactions to reactions on the comments (and leading in the process to the flourishing of so-called news aggregators).

Fourthly, bias is perceived today as the desired norm. Any reports on facts without any interpretation don’t sell: it is the interpretation of reality that sells.

This results in a haphazard flow of information existing in parallel and almost independently of reality. Several flows mean several parallel realities, with each one literally created by the disseminators of the information. Meanwhile real life and its most important aspects (for example, the distribution of resources and their use) become non-public and leave (or are removed) from the focus of public attention.

This opens up extensive opportunities to manipulate the information agenda and in the process politics for the widescale redistribution of economic power, and going forward political power. Strictly speaking, this is already happening today: such “inventions” as social networks, cryptocurrencies, “green” business, etc., redistribute hundreds of billions of dollars between specific individuals.

The degree of concentration of ownership in the new economy (See “The New Age economy”) is by virtue of the technological specifics of the economy already higher than in the traditional industrial economy, while control of the information sector makes it possible to increase this concentration even more.

The immediate outcome is that traditional political competitive models in the new environment will undergo a profound crisis. Despite the material significance of “big money”, these models were still based on open and rational agenda and implied the responsibility of politicians before elites (the proverbial “upper classes”). Today everything is changing, has already changed to a large extent, but something else will also change: the key is that at present it is unclear how everything will play out in the near future. However, it is highly likely that any attempts to return to the past will fail.

At the same time, in actual fact the technical aspect of the transformation is being implemented in practice through a revolution in the technical and technological foundation of the information and communications space. These changes impact society, ways and opportunities to manage them, public institutions and even the values being upheld.

Naturally, human nature could not change in such a short period of time. However, the methods used to organise people and opportunities to affect society and the system of relationships changed beyond comparison in previous decades. The forms and methods used to organise public relations through information flows and communications channels not only impacted the intensity of these relations, but also the content that they generated, including the establishment of prevalent values in society. Above all, we have been observing this everywhere recently.

If we put to one side technical aspects, the key development and continuing change is the abrupt decrease in social and institutional barriers for access to the mass information business. Today, in order to publish and make accessible any information content to the broadest audience — reports on actual or imaginary events, and also discussions on practically any topic — there is no need for major financial investments, lobbying or the support of society (neither society as a whole or even individual segments).

Now this is accessible to virtually any individual, even someone with modest means or a minimum level of intellectual development, as demonstrated by the hundreds of millions of users who express their views on a regular basis on social networks and other online platforms.

Such democratisation of the information and communications space results brings it closer to the expression of spontaneous mass consciousness. As a rule, the new platforms and channels have no filters, and if there are any, then they are partly or fully circumvented by anyone interested in doing so.

The underlying causes can be found not only in the development of information technologies. Traditional mass media, political structures and politicians have been more than willing to adopt the ideas of the new media formats, and have used them to popularise and broadcast their views to the masses. In particular, the elites have toyed for a long time with populist slogans and promises. The problem is not only that politicians made promises, but did not keep them (like the promise of former British Prime Minister David Cameron to cut immigration). They fed populism and used it to attain their goals and win elections: Cameron himself exploited for a long time the promise to conduct a Brexit referendum as a populist lure for the electorate. At the time, this might have looked like the right move, “going with the flow” and testing out new trends. In the end, however, everything crystallised for Great Britain into a big and dangerous problem: the prospects of actually exiting the EU without any agreement on economic relations.

Owing to the lack of boundaries and filters, this inevitably results in the fact that qualitatively content reflecting the interests, preferences and perceptions of the biggest segment of the population and a corresponding conceptual framework is prioritised. It goes without saying that in principle such a phenomenon cannot be called new in history: to all intents and purposes, it does not differ in any way from the spontaneous exchange of information, rumours and fabrications in markets in mediaeval times or in public houses and taverns in subsequent centuries. However, the volume of flows of mass consciousness and possible outreach to an audience in the new formats exceeds corresponding parameters of their historical counterparts many times over, if not by an even greater magnitude.

A revolution of standards and goals has occurred in the information and communications space: concepts determined to some extent or other by the educated part of society have been replaced by perceptions of what is normal, fitting and admissible engendered spontaneously from below.

Another new phenomenon was the disappearance of the previous hierarchy of sources of information and judgments. The flip side of the widespread availability of information platforms was the fall in their public significance. Previous respect for the written word (to a large extent related to the number of print publications, which are incomparable with modern volumes of printed information) was replaced by remarkable shallowness on a par with everyday idle talk. Meanwhile the increase in the supply of studies and resulting decrease in the quality and significance of all forms of learning undermined trust in the actual institution of education as a source of qualified understanding and authoritative judgments, and put on the same level the words of the so-called educational classes and the opinion of the man on the street.

In the eyes of a rank-and-file user of new information and communications platforms, all opinions are equally meaningful, regardless of source, create the semblance of choice between them and may easily be rejected if the user disagrees with them. In other words, in the new system of coordinates the professional assessment of an expert who has dedicated his life to studying the specialist subject under discussion is worth almost as much as a banality repeated for the thousandth time by a dilettante or the judgmental retort of an illiterate anonymous troll on this topic.

The British sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman also noted several years ago: “Orthodox brainwashing was aimed at clearing the site of the relics of old logic and sense, so as to make it ready for the construction of new logic and sense. Present-day brainwashing is keeping the site permanently void and barren, admitting nothing more orderly than a haphazard scattering of tents as easy to erect as to dismantle. It is no longer a one-off purposeful undertaking, but a continuous action holding its own continuity to be its sole purpose.”1Zygmunt Bauman, Leonidas Donskis Liquid Evil, Saint Petersburg, Ivan Limbach Publishing House, 2019, pages 60—79.

At the same time, the spontaneity of the new information and communications environment does not imply a neutral attitude to the content being put out. Human consciousness is not a clean sheet of paper: perception of external signals is susceptible to the strongest impact of instincts, fears and prejudices. Some elements of the media space are instinctively rejected or called into question, others are accepted readily and even enthusiastically as they fit the matrix representing the world most comfortable for the consumer of the information. Naturally, the configuration of this matrix is not the same for everyone — there are numerous variations, cultural codes enshrined in education. However, the laws of large numbers make it possible to compile a picture of the most typical and effective combinations. This creates the premises for the effective manipulation of mass consciousness, the dissemination of preconceptions and opinions, and as a result management of social behaviour.

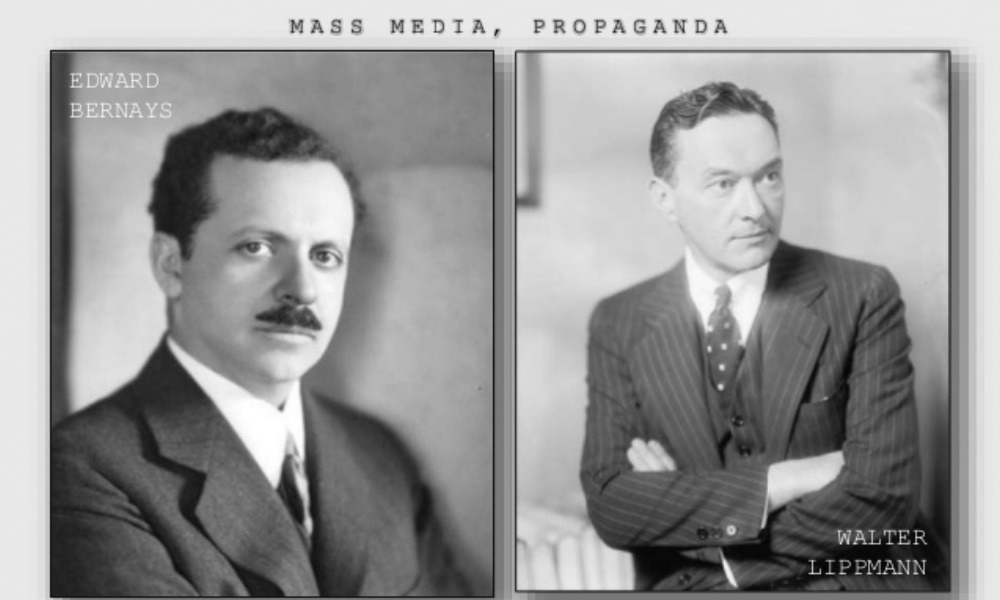

Approximately a hundred years ago this was noticed by observant experts. One only has to recall the Americans Edward Bernays and Walter Lippmann, the biggest public relations specialists in the 20th century2Bernays and Lippmann worked together at the American Committee on Public Information.. “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society”, wrote Bernays in his work Propaganda3Edward Bernays, Propaganda, Routledge, 1928.. Lippmann is primarily known in Russia for his concept of public opinion, which became a classic, and also for popularising the concept of a stereotype. Subsequently, these concepts were proactively used by advertisers and marketers, and then by politicians as well (albeit instinctively, without a theoretical base: it is highly likely that various rulers have used corresponding techniques at the very least for several hundred years). The specifics of the current stage are that the empirical experience tried and tested in advertising and political technologies can now be combined with vast network platforms, without any material financial costs, guaranteeing access to audiences running in the millions. And this is all happening against the backdrop of modern popular consciousness freed from the boundaries imposed on it by social hierarchies and the traditional mass media that they control.

Consequently, in the context of frequent crises and the psychological uncertainty of the masses, when confronted by various threats (military, political, economic, environmental, terrorist and other), which are proactively spread by an “extensive” information environment, factional groups with limited interests, who lack both political power and material economic resources, may have gained a chance for the first time in history to dispose of tools to manipulate the consciousness of millions of people and, accordingly, significant historical processes.

For the time being, nobody is ready to predict the consequences of such a revolution of opportunities — who will be able to leverage these tools to the full and how. Clearly, however, many people have motives for leveraging these new opportunities.

In the West this concerns first and foremost forces aggressively playing the card of boundless populism. Frequently, this happens in a combination with different extremist, fringe and sectarian forces interested in spreading their influence, but not disposing of major resources and the legitimacy required to act using conventional methods in legal public politics. In response, in public discourse pent-up demand for security is strengthening against a weakening desire for freedom (for example, the mass protests in the USA under the slogan of Black Lives Matter frequently accompanied by disorder and violence exacerbated this problem in American society). From the state’s perspective, sooner or later this translates into the tightening of regulation and controls. And these measures will find more and more public understanding, if not support. A tolerance of everyday restrictions and possible interference in private life has increased, inter alia, in the educated strata of society. It is highly likely that political restrictions will similarly be adopted without any major outcry.

Finally, solidarity in the upper tier of society has weakened. The elite is unable to consolidate in order to block politicians who are trying to take power, relying on the moods of the masses (the lowest common denominator), including an anti-establishment thrust. And this leads to a surge in populism. Why this happens is a different issue. However, the simple fact remains: the ability of the traditional elite to safeguard its role as the ruling class (“politically responsible class”) from different foreign elements (in ideological and cultural aspects) has weakened significantly.

Meanwhile everyone knows that as a matter of fact populism easily segues into fascism (scientifically, the ideology forming an authoritarian state, monopolisation in the economy and politics, assertions of a global mission). “We are the best because we have been told that we are the best” — that is how messages from on high are perceived by the people. And this leads to the “unity of the people and the powers-that-be”, and the fight against contrived imaginary external threats as the meaning of statehood, and the fight against betrayals and conspiracies within the country as the foundation of security, and the chain “people — party — leader” — in general, the full set of corresponding propositions. All this worked in the past and is working now, which means that it will also work in the future. And it is not at all essential that these processes assume explicit or grotesque forms: from the outside, the movement may be barely perceptible, frequently actually unperceivable. Furthermore, the façade may remain the same, notwithstanding changes to the content. In general, it can be assumed that the world, and the West in particular, already expects major shocks in the immediate future.

It is worth noting that when the system stopped delivering previous results, in the West people would blame cyberattacks and the interference of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, who were allegedly able at the drop of a hat to undermine democracy in Western countries (local activists against the “sabotage” of Eastern authoritarian regimes use this to remind our fellow citizens who are nostalgic for the USSR and are convinced that the Soviet Union was destroyed by foreign secret services). In the worst-case scenario, the actions of greedy bankers who forced the masses to pay for their financial losses from crises are cited as the reasons why liberal societies “have lost their legitimacy in the eyes of their citizens”, as a result the masses became aggrieved and voted for Trump and likeminded individuals.

It is true that populists and political opportunists existed in the past. As a rule, however, they were prevented from rising to the political Olympus by filters set in place by party systems and the “big press” owned by politically responsible businesses. In those conditions, the frustration that would intensify now and then in society did not reverse the Western political system.

So what is causing the deformation of former reliable political constructs in Western countries? Clearly, first and foremost the material and growing lag of the opportunities of modern man compared to the information and communications and digital technologies that he created over previous decades.

In particular, these are technological changes in the social and information environment, creating opportunities for politicians to recruit proponents, bypassing the “serious” mass media which have weakened considerably; uncontrolled primaries destroying the identity of political organisations; the opportunity to use political and social-psychological technologies to target audiences directly; the lifting of previous political and moral taboos, barriers based on traditions, different filters (including monetary ones) as a result of the totality of the use of the Internet with its impersonality and anonymity. And that leads to everything today called in the West the “crisis of liberal democracy” (See «On the political systems of the New Age»).

In Russia new platforms are also engendering different temptations for the most diverse interest groups. For example, in the case of the protest-minded public, this is expressed in a rejection of serious politics and a desire to develop civil activism and pseudo-political concepts in various forms of network space. However, the criticisms and protest moods that can be found on online platforms and on social networks, and even protest actions offline should not mislead anyone: in general, virtually the entire media space in Russia is controlled by structures linked to the powers-that-be and in the end meet the interests of the ruling regime. Admittedly, the latter circumstance is frequently masked by repressive measures against various platforms. As a result one may gain the impression that there is real confrontation between the authorities and certain representatives of Russia’s IT sector.

It is another matter that the heterogeneity of the ruling elite engenders constant friction within when different groupings “plant” information online in a bid to consolidate their positions. This can range from all manner of anti-establishment attacks and constructs — from moderate criticism of the regime to over-the-top assertions, exposures, insinuations about mythical conspiracies and the underhand practices of a “shadow executive” and “world governments”.

These days such attacks change little in the real world. However, this does not mean that this will always be the case. Similar to the destructive potential of weapons of mass destruction, at some stage their owners give in to soaring ambitions and unsubstantiated aspirations to exert global influence, as opportunities to effectively work with the collective consciousness will trigger the temptation to exploit these tools to implement various attempts at political coups for the redistribution of power and property.

Society is entering unchartered territory, and the most varied turns in events, including unpredictable developments, are possible. However, it is already clear today: the increasing information ochlocracy will not result in freedom for society, enable people to live their lives without fear or result in respect for the individual.

POLITICAL ENTROPY

Digital technologies and the globalisation of disorder

- INTRODUCTION

- ON THE POLITICAL SYSTEMS OF THE NEW AGE

- THE PANDEMIC AND POLITICS

- INFORMATION OCHLOCRACY

- THE NEW AGE ECONOMY

- MASS PROTESTS AND THE MODERN WORLD

- WHAT SHOULD BE DONE? INSTITUTIONALISATION OF VALUES