WHAT THIS TEXT IS ABOUT

The introduction of President Putin’s amendments to the Russian Constitution signalled the defeat of the democratic reforms commenced in Russia at the end of the 1980s – start of the 1990s. This failure can be attributed primarily to the following factors:

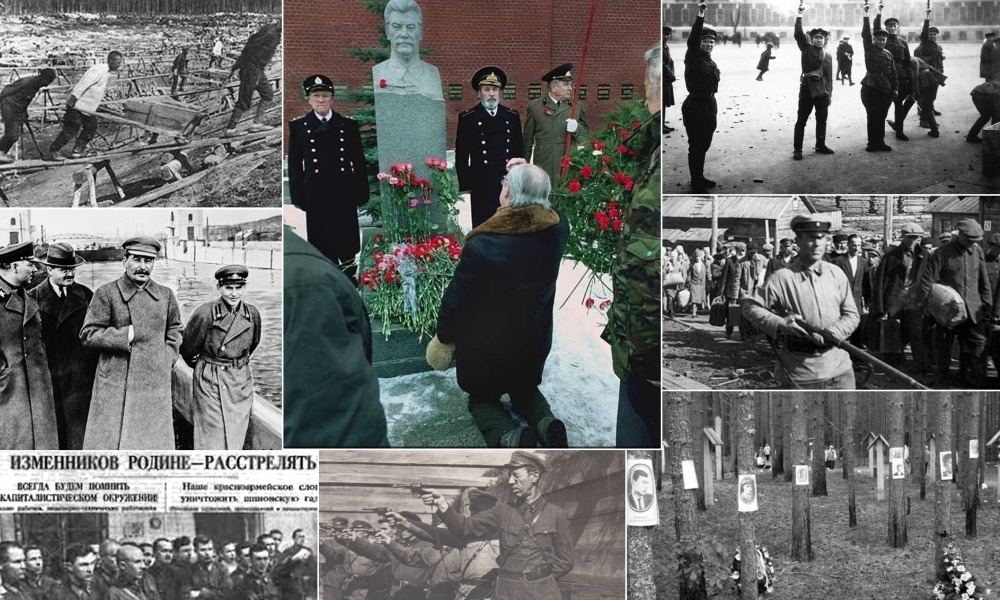

- The refusal to conduct a state and legal assessment of Stalinism and the crimes of the Soviet period;

- Gross miscalculations in the logic and substance of the reforms of the 1990s: hyperinflation, the loans-for-shares auctions, the merger of the state, property and business, and the emergence of an oligarchy.

These factors underpinned the creation of an autocratic, unlawful, quasi-mafia and anti-social political regime in Russia, marked by chronic economic stagnation and an impoverished population. This also led to a political system dictated by an imperial mindset, adherence to the principle of the “limited sovereignty” of former Soviet republics, attempts at flagrant interference in the affairs of neighbouring countries, the annexation of Crimea and war in the Donbass, contract killings of political opponents and journalists, senseless bloody participation in the war in Syria, and the adoption of countless repressive and backward-looking laws.

The goal of the opposition in the new environment is to engineer the regeneration of the Russian state: convene a Constituent Assembly; adopt a legitimate Constitution which actually exists to serve the people; and build a modern country on its basis. To succeed, we must achieve the following objectives:

- Prepare the draft of a new democratic Constitution;

- Start the work required to prepare, convene and hold the Constituent Assembly (with the participation of all the political forces in Russia capable of submitting their proposals on the structure of the state — from a constitutional monarchy to a parliamentary republic, and also propose corresponding drafts of constitutional acts for discussion);

- Conduct the broadest possible outreach campaign on the need for the state and society to evaluate Bolshevism, Stalinism and the whole Soviet period;

- Draft and start promoting an economic reform programme (which proposes the unconditional reinforcement of the right of private property, a material decrease in the role and extent of the state’s presence in the economy, and the implementation of a range of measures based on the proactive social classes: the industrial elite, financial community and entrepreneurs);

- Develop reforms of the judiciary and the Federal Penitentiary Service, and prepare amendments to the Criminal Code;

- Free the mass media from state control.

The democratic opposition should no longer play the role of adviser or consultant to the authorities. Politically, the regime must be forced into dialogue with the opposition. It is important to develop a modern political party, practice modern public politics and train new politicians. The end of the era lost by democratic forces must be transformed into the start of a new era. For this purpose we need a new course of action, different priorities and a principally new departure in politics. The key talking points are set out in this article.

INSTEAD OF AN INTRODUCTION

The events of summer 2020 draw the line on an entire era and emphasise clearly the intentions of the post-Soviet authorities in coming years. Fraud has given way to outright and base lies. The narrative “We will never leave” has become the universal response of the authorities to any demands for change.

In Belarus and Russia the situations are to all intents and purposes very similar: the authoritarian regimes are unable to conduct dialogue with society; they are preoccupied with only one issue — self-preservation. Hundreds of thousands of Belarusians protesting against the lie in the elections and incensed at the violence took to the streets in August. However, the benign patriotic protest came up against a totalitarian machine of suppression, ready in the defence of the regime to deal ruthlessly with its own people.

It is clear from the painful example illustrated by Belarus how civil protest is in dire need of politics, a political component. And this means more than simply the formal lack of any opposition bodies or declarations which could be created rapidly “in line with the situation”. Political substance is not some vignette or brochure, but instead the linchpin of an alternative, the foundation of an ideology focused on the future, and a reform programme, which is an indispensable premise for the existence of a political party led by a serious and respected leader who is prepared to fight and win. It goes without saying that an essential component of any real protest is the inclination and resoluteness to take to the streets, and the more people driven by this desire, the better. However, while this is a necessary factor, it is not enough. A widespread informed idea, political programme of the opposition and leader are required. Otherwise, even the most sizeable and impressive demonstration of protest and of civil disobedience are incapable of engineering regime change. Politics represent the only way to achieve real change.

Both in Russia and Belarus the immutable regimes have for decades been scorching the political field, destroying politics, depoliticising their citizens and killing off any substantive alternative to the ruling authoritarian model, and have deliberately led society to political degradation. Moreover, the Kremlin’s reaction to the events in Minsk is merely a continuation of this line. The Russian authorities claim that “the internal problems in Belarus” can only be resolved by the “leadership of this country through dialogue with its citizens”, while declaring at the same time their “consent with any decision adopted by Lukashenko”. And we can see how Lukashenko is conducting this “dialogue”, brandishing an assault rifle and calling Belarusian citizens “rats”. To all intents and appearances, such a model of “communications” between the authorities and the opposition, and for that matter, with all independently-minded citizens, will be implemented in Russia in the coming years: the brutal suppression of any protests, repressions, tortures, attempted assassinations, poisonings and murders. The current situation with Alexey Navalny merely proves the point.

That is the reason why anyone concerned about the future of our country should once again start engaging in serious political work. Above all, we need to understand the reasons for the failure of post-Soviet modernisation and now determine with our eyes wide open how we must act in the current environment. And it is only then, when the country stirs up once more and when the necessary conditions have been formed – as was the case in Russia in 1990 and in Belarus in 2020 – that the people will finally win: acquire freedom, democracy, justice and respect.

THE END OF AN ERA

On 1 July 2020 the Russian state, which had existed for almost 30 years after the end of the Soviet Union, was dismantled once and for all: the repudiation of the formal commitment to democratic legitimacy, federalism, and the onward movement from the Soviet past to a modern civilisation of the 21st century, was formalised officially.

The immutability of the personal power of Vladimir Putin is now enshrined in the country’s Constitution which spells out the basis for a corporate quasi-mafia and super-authoritarian state, backed by a chauvinist ideology.

It has to be admitted that such an outcome was virtually inevitable: this is the logical

consequence of a number of key decisions adopted at state level in every single post-Soviet year (see the timeline below). The era of post-Soviet modernisation of Russia has ended. Democracy has been defeated.

EVENTS THAT PRETERMINED THE SITUATION ON 1 JULY 2020

1. Rejection of the Russian programme for the transition to a market economy and the Economic Treaty with the former USSR Republics on the establishment of a common market: instead – in exchange for IMF loans – implementation of an economic reform plan based on the prescriptions of the Washington Consensus concepts, which were at variance with Russian realities.

2. The headstrong, unprepared and irresponsible signing of the Belovezha Accords: the virtual complete destruction of economic ties with former Soviet republics.

3. Refusal to conduct a comprehensive state and legal evaluation of Bolshevism, Stalinism and the Soviet period, the large-scale retention in power structures of Soviet party functionaries who had “changed their colours”.

< navigation on the timeline from right-to-left using the arrows >

RUBICONS OF THE DEFEAT

The post-Soviet reforms resolved a number of consumer objectives: they filled the stores, guaranteed the accessibility of the simplest services, created a real market of goods and services, albeit limited and monopoly-based, which was linked to external markets (foreign trade). To all intents and purposes, oil and gas were exchanged for more and less full shelves in the stores…

However, from the perspective of the economy as a system, the goal of achieving a new professional economy and improved living standards was not resolved. The post-Soviet modernization failed in full-fledged economic and almost in any human way.

During the past 30 years, the living standards of 15-20% of the population have improved materially – first and foremost, the residents of Russia’s capital and some other major cities, and also of anyone involved in the extractive industries and financial sector, the “elites” of different areas, and state officials.

At the same time, the living standards of the absolute majority of the population (80-85%) have remained low during these decades, and even started falling during the past few years.

Incidentally, the events of 1 July 20201Following the plebiscite on 1 July 2020, amendments to the Russian Constitution were approved. One of the amendments reset Vladimir Putin’s terms as Russian President to zero. As a result, once his current term ends in 2024, he will be able to stand as candidate for Russian President for another two terms and effectively remain in power until 2036. signalled for a number of people the end of the era of false dawns. People will become aware of this situation in some way or other and change their behaviour accordingly.

Very little has been achieved in the high technology sector. The international success of Russian technology projects is to the credit of private developers who have managed to succeed, notwithstanding the state system, and by no means thanks to its input.

Achievements in the military industrial complex are also dubious. The presentations by President Putin of new weapons, using animation and special effects from the film industry, carry little credibility, and instead instil fear. The key strategic resource of Russia’s military industrial complex is as in the past the vast nuclear arsenal created in Soviet times, and not new developments. Furthermore, the real threat of the destruction of the country and death of the population as a result of nuclear war is intensifying as the global nuclear security system collapses (see The Threat of War, 2019). The likelihood of regional wars on the perimeters of Russia’s borders has increased. Thirty years after the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan, our compatriots are fighting in Syria, Libya and the Sudan.

When the movement for change started in the 1990s, the underlying motive for this process was the development of mankind and the realisation of the nation’s intellectual and creative potential. However, the key tenets in life had not been achieved by 2020:

- We are not free;

- We live in fear;

- There is no respect for the individual;

- We have no confidence about our prospects going forward and the future of our children;

- We find ourselves undefended from arbitrariness;

- We have no courts that inspire trust or allow us to expect a fair trial;

- Individuals have no influence over the authorities in the country, over the specific decision-makers or their actions.

The truth is that the democratic reforms which started in Russia three decades ago ended in failure.

REASONS FOR THE FAILURE

When talking about the reasons for the failure of democratisation in Russia, it goes without saying that people tend to cite the historical and cultural specifics of our country2See G. A. Yavlinsky, A. Kosmynin, Notes on History and Politics: The People, the Country and the Reforms. Мoscow, Moskovskiye Vedomosti, 2015, and also global political and economic trends over the past three decades3See G. A. Yavlinsky, The Recession of Capitalism – Hidden Causes. Realeconomik. Moscow, HSE Publishing House, 2014.. These factors are indeed material, but at the same time they are not pivotal. They merit a separate discussion.

The key reasons for the collapse of post-Soviet modernisation – and simultaneously the most important political phenomena of 1990-2020 – are as follows:

- The outright refusal to comprehensively evaluate and make a clean break with Bolshevism, Stalinism and the crimes of the Soviet period; continuation of Stalinist-Bolshevik state policies and modern Bolshevism (see The Great Terror and Modern Bolshevism, 2017); the framing of the Soviet-Bolshevik legacy as the basis for sovereignty, equated with the inviolability of personal power; the rejection of dialogue as a political tool, an understanding of political competition only as an encroachment on power, and an independent judiciary as a source of potential danger; the failure to replace the elites after the disappearance of the USSR, the accumulation of the former Communist Party and other Soviet officials around Boris Yeltsin who was by himself the candidate for the Politburo membership (the highest Communist authority in the Soviet Union).

- Gross miscalculations in the logic and substance of the reforms4See I. Nikolayev, Starting with the End. What Did Russia Achieve After the Collapse of the USSR? Novaya Gazeta, July 2020; G.A. Yavlinsky, A.V. Kosmynin. Twenty Years of Reforms. World of Russia. Mir Rossii, 2011, No. 2-3.: over-estimation of the extent of the economic transformations and actual adherence to the Marxist thesis “the base determines the superstructure”; failure to adequately assess the need for political reform, thorough restructuring of the judiciary and administrative system, radical changes to the security service, the defence of freedom of speech and the mass media from actual censorship, and the implementation of crime-fighting and anti-corruption policies; the retention of the high-level positions continuity.

The rejection of an independent Russian economic reform programme played a particularly important role. And this happened despite the fact that the country had its own intellectual potential to develop such reforms and disposed of the human potential required for the implementation of this programme, and despite the unique nature of the economy to be reformed. Why? This was due to total distrust of internal forces (above all in people) and blind adherence to one-size fits all solutions, combined with psychological dependence on external approval and loans from the West.

This is the reason why the 500-day program5Program was developed for the reform of the USSR, envisaging transition “at the expense of the state, rather than ordinary people”, the first stage of the program envisaged massive small and medium sized privatisation using personal funds accumulated during the Soviet period, distribution of the state property among the people and creation of the middle class, price liberalisation was to be carried out simultaneously with privatisation and had to stabilise the market and create prerequisites for economic recovery. was not implemented and why the Economic Treaty between Former Republics of the USSR was not adopted.

In autumn 1991 the heads of thirteen former Soviet republics (the Baltic states attended as observers and the remainder as participants) signed an Economic Treaty and a package of special agreements to the Treaty. The Treaty stipulated the creation of a banking union, the introduction of a common currency (the rouble), a single customs space, free trade, a common market and common legal space throughout the former Soviet Union.

As a result of blatant economic errors, conscious and unconscious criminal decisions, adherence to frequently politically motivated foreign recommendations supplemented by loans, instead of establishing the basis for a modern market economy in Russia, the foundations were laid for an oligarchic mafia-based corporate authoritarian system. The largest blocks in this foundation were:

- The Belovezha Accords and the severance of economic ties between former Soviet Republics in 1991;

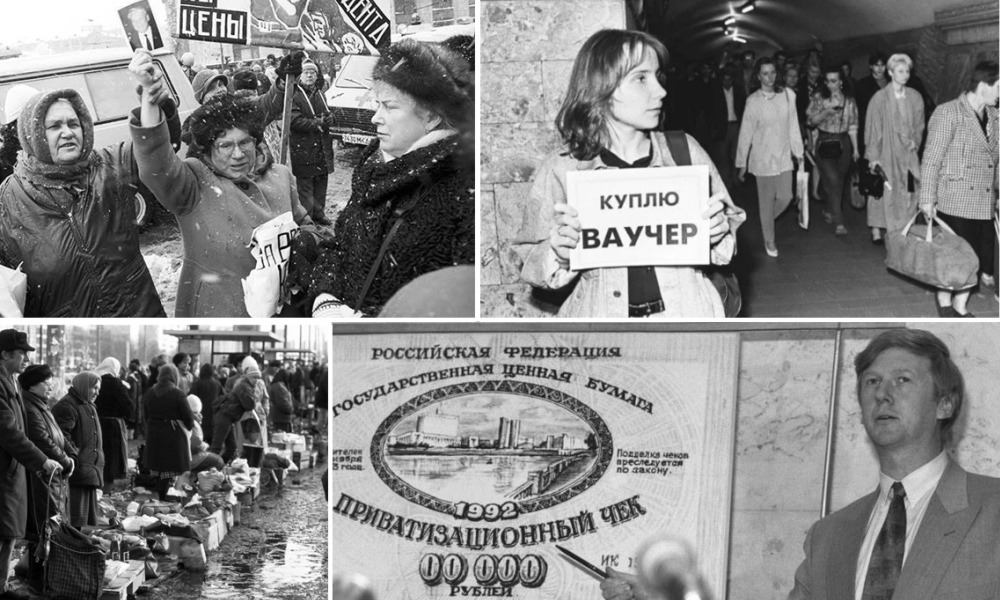

- Confiscations of the savings of Russian citizens as a result of 2,600% hyperinflation in 1992;

- Voucher privatisation instead of the mass sale of actual property on terms and conditions that were acceptable to the people and the definitive elimination of the premises required for the emergence of a middle class;

- The loans-for-share auctions and the emergence of an oligarchy;

- The merger of the state, property and business, the transformation of the state authorities into the key oligarch and, as an inevitable consequence, the absence of the necessary conditions for the establishment of an independent judiciary and independent mass media, and the disinterestedness of the ruling regime and big business in their existence.

“FIRST OF JULY” SYSTEM: GENESIS AND STAGES OF ITS FORMATION

As a result of the failed reforms, a hybrid political system has been formed in Russia, consisting of:

- Soviet, national-Bolshevist political models and institutes;

- Primitive half-baked market capitalism;

- Wide-ranging corruption-based relations inherent in regimes where there is no independent judiciary and free press;

- Oligarchy, in other words, big business effectively merged with the ruling regime.

After 1993 understanding of the state as a corporation (mafia state) based primarily on the exploitation of available resources emerged and started to be implemented in practice (furthermore, the people are also perceived as a resource). The key objective of such a state is to retain power and ward off any potential challenges.

This was the basis for the system of Vladimir Putin and his immutable regime, which was in the end formalised and enshrined in the Constitution of 1 July 2020 (See Legitimating the Corporate State, March 2020). This is the predictable result of the past thirty years. The key landmarks in the drive towards the “First of July Regime” can be determined as follows:

- Rejection of political compromise in the country in 1993 and the war in Chechnya;

- Electoral fraud at all levels, through use of the administrative resource and propaganda machine to attain corporate goals in 1996, 1999, 2000 and all subsequent years;

- Retention of the systemic shortcomings in the legitimacy of the state and compensation through support based on lies and violence;

- Selection by Yeltsin of a KGB employee to guarantee the preservation of the created system and continue the process;

- Personnel policy based on the priority of loyalty, subordination and an ability to fit into the system;

- Implementation of the understanding of power as authoritarian ‘vertical’ power, suppression of political opponents, using all available means, up to and including physical elimination;

- Monopoly control over the mass media: media wars involving the state, which were the direct result of the merger of state and property, and the inevitable victory of the state as the strongest player;

- Politics dictated by an imperial mindset, adherence to the principle of “limited sovereignty) of former Soviet republics, attempts at flagrant interference in the affairs of neighbouring states, the annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbass.

Consistent disregard for the institutes of a democracy and civil society has resulted in the replacement of fundamental values with the formation of President Putin’s concept of post-Soviet history, which attributes the collapse of the Soviet system to some vague reasons, in all likelihood due to a “conspiracy” and “enemy plots”. Now, after all these experiences, it was allegedly necessary to “rise up again”, “restore sovereignty” and move along on our own “unique path” (this is the inferiority complex which was formed in Russia for internal reasons, but today partly goes in hand in hand with a global trend). However, Putin’s regime has not created and is unable to create an alternative to the European model – from the perspective of both implementation and development (see “The Path That Wasn’t There”, 2015).

Such a post-modernist model divorced from reality merely satisfies the personal ambitions of a limited number of people. Victory in World War II was selected as the ideological centrepiece for this model (see “Victory Parade Ideology” , June 2020). This is how the Kremlin’s functionaries plan to exploit the readiness of people for self-sacrifice for the sake of the state’s interests, create in society an atmosphere of hate and a state of permanent war with the West, and against the backdrop of this confrontation, secure the submission of the population to the bureaucratic top-down system, which imagines itself to be a state.

It is clear that such a construct can only exist if you have significant resources. The longstanding economic stagnation, reinforced by the regime’s refusal to support the economy and business during the Covid-19 pandemic, combined with Western sanctions and Russia’s increasing technological inferiority compared to developed countries, casts doubt on the adequacy of the resources available for such a protracted period. The transition to some kind of mobilisation model, and the accumulation by the ruling group of the most important resources and their distribution at their own discretion will be required. This will imply the overt opposition of the interests of the ruling elites to the interests of a population that has been impoverished for so many years: people may not agree to any further decline in their living standards for the sake of the endless need to “stand on our own feet”. All the more so as society is becoming more and more convinced that Putin’s regime (especially after the constitutional quasi-legal registration procedure on July 1 2020) is devoid of any prospects going forward.

If the collapse of this system is only a question of time, the form in which this happens is unclear. The objectively unstoppable growth in discontent from below, combined with the regime’s fixation on self-preservation, the protracted deliberate design of a repressive machine and the consistent destruction of politics per se – this is a toxic mix. Our understanding of this fact is compelling us to do all we can to prevent any bloodshed. Violence and any victims during regime change would not enable the country to move forward normally.

To avoid bloodshed, the active part of civil society already needs to rebuild democratic politics today (See “Activism and Politics”, 2019), and organise an alternative that is comprehensible to most of the country’s citizens.

A NEW START: “PROGRAMME OF THE SECOND OF JULY”

Russia’s natural development was interrupted in 1917 by the criminal Bolshevik overthrow and the shutdown of the Constituent Assembly. It will only be possible to continue moving forward through the restoration of democratic legitimacy and the creation of a state that represents a continuation of civil society6See G.A. Yavlinsky, A.V. Kosmynin. The Prospects for Russian Society in the 21st Century: Terminal Exit or Modernisation. “Mir Rossii, No. 3, 2011..

The fall of the Bolshevik system, the liberation of Eastern Europe from communism, materialisation of the aspirations of the peoples of the Soviet republics for freedom at the end of the 1980s – start of the 1990s – represented a shift in the course of history. This was an inevitable consequence of the unviability of the Soviet system. At the same time, these socio-political processes were driven by the desire of late-Soviet society for a clearly defined change: democracy, society’s control over the authorities, a market economy, equal opportunities, an increase in living standards and the quality of life.

This is the sine qua non7Sine qua non — an indispensable and essential action (Latin). if we are to move forward. Otherwise, Bolshevism and Stalinism will not be overcome, the oligarchic system will not be dismantled, while any goals will remain demagogic and false. Such goals will once again be justified through any means. And this will mean that we will endlessly go round and round in circles pointlessly.

Such an assessment is not some theoretical assumption: it is confirmed by almost thirty years of political experience. Existing in a corporate mafia system, trying as much as possible not to be part of the system and aware of our responsibilities, we perceived the significance of politics as an attempt to adjust the direction of travel of our country to a more positive destination. Yes, it is arguably the case that we were unable to change the country’s trajectory. At the same time, however, all our political assessments and forecasts turned out to be true, the substance of the democratic alternative that we created still remains topical.

We did not support the 1993 Constitution, because we believed in the need to create a more solid foundation of the new Russian state. This concerned both the democratic aspects and legal nature of the substance of the Fundamental Law, and also the involvement of the broadest possible range of people in the development of the Constitution and the foundations of the state – and not some extras who simply need to approve something that has already been proposed.

We fought the pernicious reforms that served the interests of a small group, and advocated reforms to serve the needs of the majority throughout the 1990s. We acted within the constraints of the established conditions and tried to facilitate evolutionary change. And we lost. However, what we created during all these years – programmes and draft laws, and most importantly the vector setting the course of honest social liberal politics (individual freedoms, living fearlessly, creativity, shared understandings) – today represents a real basis for moving forward, provided that there is the political will to do so. The point is that we have developed a democratic alternative to Putin and his focus on war, the militarisation of society and intimidation for political goals. We have substantiated publicly and advocated an alternative course of development of the state.

Now, after the 1 July plebiscite approval of the amendments to the Constitution, we find ourselves in a new environment. And here two fundamental facts must be noted.

- After the “vote”, on 1 July, a law-based state has been repudiated in Russia, electoral procedures have to a large extent been transformed into a sham, parliament has become a mere appendage and enforcer of Putin’s decisions. The Presidential terms were not the only things to be reset to zero – the State Duma, regional legislative assemblies and the Constitutional Court were also reset to zero. We will have to exist against the backdrop of a purely decorative parliament.

- The objective conditions for political work have changed materially. This is attributable first and foremost to the appearance of principally new information, digital and communications technologies (including big data technologies). Globally, these circumstances have increased abruptly the impact of populism and nationalism and have in general materially debased the quality of politics. The new trend is also due to the significant contraction of the political arena: elections have lost their former significance, while participation in them can now be viewed first and foremost as a way to train staff and only to a minor extent as a way of influencing politics. In Russia the combination of the super-authoritarian governance model with an aggressive police state and new technologies sets extremely complex challenges for politicians.

The following should become the programme objectives of the core of a democratic opposition:

- Prepare a democratic social and liberal Constitution which reflects the realities of the modern world, the specifics of information and digital technologies focused on the young, taking into account both the negative and positive experiences of the 1993 Constitution. This document should rely as much as possible on the norms of direct action, which make it possible to achieve freedom, foster creativity, respect for each other, enable people to live without fear, and also institutionalise fundamental values, such as a ban on torture, the abolition of army conscription and the transition to contract-based military service (see Constitution of Free People);

- Conduct comprehensive political work to convene and hold the Constituent Assembly, with the participation of all the political forces in Russia capable of submitting their proposals on the structure of the state, from a constitutional monarchy to a parliamentary republic, and also propose corresponding drafts of constitutional acts for discussion. During an extensive and multidimensional discourse, popular discussion, public and professional political debates, the key norms will be developed with due account of public opinions, which may subsequently be adopted by the Constituent Assembly. It is clear that the preparation of such a Constituent Assembly will take several years, and that the battle to convene such a body will prove very difficult. However, the restoration of Russia’s real legitimacy and termination of centuries-old state lies and transgressions is a key historical objective (see «Lies and Legitimacy», 2011; “February Parallels” , 2007);

- Carry out constant comprehensive political and awareness-building work to clarify the need for the state and society to evaluate Bolshevism, Stalinism and the entire Soviet period. The democratisation of the country is impossible without first making a clean break with the Stalinist-Bolshevik legacy. Bolshevism would return as Neo-Bolshevism, post modernism, “flexible evil” (See “Overcoming Stalinism”, 2009; The Great Terror and Modern Bolshevism, 2017);

- Draft an economic reform programme, including the unconditional reinforcement of the right of private property; a material decrease in the role and extent of the state’s presence in the economy; increase in competition and demonopolisation; optimisation of tax and monetary policy; rejection of the conservation of resources for emergencies (armed conflict and other confrontation); draft a range of measures based on the proactive social classes: the industrial elite, financial community and entrepreneurs; draft a system of measures to separate the state from business and property, in other words, eliminate the key reason for the collapse of post-Soviet modernisation – the merger of the state and property8See G.A. Yavlinsky.“Need and Ways of Legitimatising Big Private Property in Russia: Definition of the Problem, Voprosy Ekonomiki, No. 9, 2007; G.A. Yavlinsky. “Recession of Capitalism”, National Research University Higher School of Economics, 2014; G.A. Yavlinsky. Russia’s Future. Economic and Political View”, Galleya-Print, 2006; G.A. Yavlinsky. “Incentives and Institutes”, National Research University Higher School of Economics, 2007.;

- Draft reforms of the judiciary and the Federal Penitentiary Service; prepare amendments to the Criminal Code; free the mass media from total state control; introduce improvements to the migration control system, establish an institute for the adaptation of migrants; protect the rights of migrants9See S.A. S.A. Gannushkina. Why do Russian Residents Request Asylum in Europe?, 2019; The Pandemic Contributed to the Release of 50% of Migrants from Temporary Holding Centres of Foreign Citizens, 2020.;

- Prepare reforms of the electoral system10See. E.P. Dubrovina. Proposals on the Reform of the Electoral System of the Russian Federation, 2019.;

- Implement measures to normalise Russia’s international standing (Crimea, Donbas, Syria), and a range of political measures for the revocation of the sanctions against the country11See the Special Project “Is Crimea Ours? ; G.A. Yavlinsky. Settlement of the Situation in the Donbass. 10 Points, 2010; G.A. Yavlinsky. “War in Russia: What Needs to be Remembered” , 2019; A.G. Arbatov “Coronavirus Will Disappear, But Nuclear Weapons Will Remain With Us, 2020.;

- Establish an environmental programme aimed at reducing climate risks which are becoming a more and more decisive factor for the country’s long-term economic and survival prospects;

- Form, train and prepare a body of politicians of the new era – people, whose values will differ radically from the mindset and actions of the functionaries nurtured by Putin’s system.

To put it another way, after 1 July 2020 the key objective is the preparation, political articulation and promotion of a full range of measures aimed at the construction of a new Russian state. This objective had been planned after the end of the Soviet period, but was not achieved (or was achieved, but with glaring, and in some cases, criminal errors). An understanding of the committed errors and reasons for the collapse of the post-Soviet modernisation is extremely important.

NEW OBSTACLES

The most recent events have highlighted yet another consequence of the failings of post-Soviet modernisation – the political degradation of society. The point is that the completely justified discontent of the people with the actions of the authorities is not manifested through politics – not through the informed refusal to support the absurd amendments to the Constitution in 2020, not through voting against Putin in the Presidential elections in 2018 and also not through protests against pension reform. Instead, popular discontent spills out through spontaneous mass actions in support of a bureaucrat from the criminal Liberal Democratic Party of Russia who was popular in his region, which is interpreted by a significant proportion of the Russian capital’s opposition activities as the start of a democratic movement against tyranny.

In actual fact, this is the result of the protracted political dumbing down of Russia’s population through propaganda, the involvement of the people in the “Crimea Spring” euphoria, the triggering of a war in the East of Ukraine, participation in the war in Syria, and constant state lies on all material issues. Against the backdrop of such intensive and aggressive brainwashing, it is hard to engage in political work aimed at educating, explaining and convincing people of the need to engineer the rebirth of the state and transformations based on the institutionalisation of values, and the building of a modern democratic state.

We are confronted more and more frequently with the misconception that political thought is unnecessary, that politics only represents a personalised scramble for power, and that the only real action is to turn up for meetings, while true democracy will grow from street protest all of its own accord.

However, it will not emerge from such protest. And this is demonstrated by the collapse of post-Soviet modernisation. Neither the Triumphalny, Bolotny or Pushkinsky protests were able to set the political vector for street protest. Even the most large-scale protests need substance, clearly articulated political demands which are put to the authorities, and also leaders (see Activism and Politics, 2019). If society feels estranged or doesn’t want to talk about complex issues, this means that Putin and Putin’s Constitution have won, regardless of who is the actual boss at the Kremlin.

We need to offer the people an idea-driven, clear-cut and value-based programme of liberal democratic (according to the true meaning of these words) transformations and not seek to “harness” chaotic protests through manipulative technologies and any means.

Democratic thought must be present in the public and political space. It is far harder to initiate and support such a discourse than simply shouting “Down with Putin!” or engaging in vacuous disputes on who is servicing the regime and how, or who is “betraying” the protest.

The creation of an intellectual alternative, the generation of political thought, programme and substantive political slogans – this is the real action which is needed as many people correctly reason. However, very few are actually engaging in the implementation of such action.

In the case of mass activity, then recently in 2014 we observed short-term, but completely sincere activity, which was analogous to mass psychosis – the so-called Crimea Spring stridently and aggressively supported by all the parliamentary parties and their electorates. This became possible, inter alia, because people have consistently been weaned off political thought.

HOW TO ATTAIN PRACTICAL RESULTS

The issue of the practical implementation of the measures to be developed deserves a separate conversation. Experience of the past thirty years has provided a clear demonstration that political opposition should not assume the role of adviser or consultant to the authorities, such activity is extremely ineffective. Politically the regime must be forced into dialogue with the opposition. The opponents of the authoritarian regime must engage in rigid and specific dialogue with the regime from the position of a well-developed democratic alternative – an idea-driven, programme-based and political alternative. Support for such a process in the current environment will be a serious political step for all rational and responsible citizens, conceptualised by civil action and the expression of a protest position. For it is namely consistent and substantial pressure on the authorities exerted by a politically organised civil society, and not only spontaneous street protests, however widespread they may be, which will open the door initially to a serious discussion of the topical agenda among a broad spectrum of society and then through a round table format, with the regime – for real change in the country and regime change.

Three key components are required for the practical and successful (!) implementation of the new policy:

- Current professional action programme on extricating the country from the crisis and conducting effective reforms;

- A leader capable of engaging in professional dialogue on an equal footing with the regime on political and social and economic requirements, disposing of highly-skilled staff and relying on an effective political party;

- At least one million active supporters in the country.

If we don’t work on the substance of the alternative, if we don’t initiate extensive public discourse, we don’t compel the regime to engage in dialogue, then it will not possible to engineer any changes, regardless of the personalities shifts and situational power takeovers in Kremlin. Neither pickets, nor even revolutions will help. The authorities have committed so many criminal misdemeanours over the past thirty post-Soviet years that a chain of anarchic events is predetermined for many years to come. Such is the logic of the political process. If the Kremlin was able in 2014 to conduct a “referendum on the status of Crimea” in a foreign country, then why shouldn’t it conduct in 2020 a plebiscite to approve the dismantling of the Constitution and extend Putin’s rule until 2036? That is why it is entirely pointless to reason that “they simply got the number of votes wrong”.

Whoever intends to engage seriously in democratic policies after 1 July 2020 and has asked “Well, what can we do now?, here is the answer.

- Learn “not to live a lie” in public life, speak the truth about our country: about politics, the economy, the social sector, and culture;

- Defend and assert the right to life and freedom, the priority of the individual, equality before the law, respect for one’s fellow man, life without fear, creative freedom, equal opportunities;

- Build a modern political party and practice modern public policies, train up politicians;

- Proactively fight for the irreversible defeat of Stalinism and Bolshevism;

- Draft and present to society a promising comprehensive reform programme;

- Fight against the ideologies of vengeance, nationalism, chauvinism, populism and political speculation;

- Protect the public from a digital dictatorship.

It is true that the era of Russia’s post-Soviet modernisation ended in defeat. However, it is precisely now that the end of the lost era should be transformed into the start of a new one – the era of the construction of a New Russia. For this purpose we need a new course of action, different priorities and a principally new departure in politics, whose talking points are set out in this article.